WHY & FOR WHOM: Ethics of generative AI for music [Unfair use? series, PART 1]

Part 1 of our series on ethics of generative AI for music - Who's most affected by generative AI for music, why they might want to engage (or not), and why the 3Cs/4Cs matter for the ecosystem.

Welcome to the first article in our series on ethics of generative AI for music, and how it affects PRODUCTS and PEOPLE! (Updated 2024-09-24 to provide references to CIPRI and AJL for 3Cs/4Cs)

Here in PART 1, we address WHY & FOR WHOM. We will identify key stakeholders impacted by generative AI for music, and why each group might (or might not) want to contribute to it, use it, or work on it.

PART 2 will tackle how each stakeholder group is affected by ethical concerns (including biases) and how emerging guidelines and standards can help.

PART 3 will address WHAT & WHEN (products and companies). Later articles in the series will dive deeply into the ethical concerns on genAI for music, summarize, and share some recommendations.

This article is not a substitute for legal advice and is meant for general information only.

Background

Algorithmic composition of music isn’t exactly new. Computers have been “writing” elevator music and classical tunes for many years now (1997 article, 2010 article, 2015 article, Microsoft Songsmith). Even use of AI for music isn’t quite new, either:

A product called AIVA (AI Visual Artist) was created in early 2016 to generate music with AI “in more than 250 styles”.

Many AI-based tools have arisen which can help with generating a song, such as Beatoven, Soundful, Ecrett, Soundraw, and Boomy.

This page from the University of Virginia lists a broad range of tools relating to music, some using ML and AI such as Boomy, AIVA, and MuseNet.

Generative AI changes the nature of the AI-based support, though. It goes beyond helping a musician on their own songs to creating something ‘new’ based on other people’s songs.

Some of the latest AI-based music tools leverage text prompting (tools like ChatGPT) to generate audio tracks with AI. This is called TTA, or Text To Audio. A few AI music tools even use AI text prompting to generate lyrics as well as melodies. (In this article series, we’ll focus mostly on the melodies.) Here are pages with some examples: Google MusicLM, OpenAI Jukebox.

In some ways, these genAI tools for images, music, etc. are comparable to so-called “end user programming” tools, past (non-AI) and present (AI-based). Providers offer AI-based tools to enable people to achieve skilled tasks they previously couldn’t do (without developing the skills) - like writing software, drawing a painting, composing music, or producing a video. The same questions, criticisms, and risks apply:

Is that AI-generated code/image/music/video “good”, and was it created ethically?

(Answer so far: maybe, sometimes)

Generating music is technically challenging even for AI, more so than for code or images. In part, this is because of the high number of consecutive steps that must be predicted successfully to yield a good result for a song:

“A typical 4-minute song at CD quality (44 kHz, 16-bit) has over 10 million timesteps”

By comparison, GPT-2 had only 1,000 timesteps

As explained by NVIDIA’s Nefi Alarcon, the high number of timesteps means that “an AI model must deal with many long-range dependencies to re-create the sound” for generating music.

Early TTA tools were extremely slow, taking hours of expensive compute time to create a minute of audio. However, like in so many other application areas, 2024 progress in computing performance and generative AI is accelerating and taking computerized generation of music to a whole new level.

Now that the tools are becoming fast enough for ordinary music creators to use (without needing massive computing power at their disposal), use of these tools is starting to expand beyond a small core of researchers and developers. This shift is triggering new discussions about risks and benefits and ethics of generative AI for music.

Many major and minor companies and startups are now active in the genAI music space. One recent event, as of this writing, introduced another major entrant. A Feb. 28 blog post by the Adobe Research team announced a preview of “Project Music GenAI Control”, their TTA-based “new cutting-edge generative AI tools for crafting and editing custom audio”.

The participants in this space and their offerings will be detailed in Part 3, WHAT & WHEN, in this article series. Parts 3-7 will focus on ethics aspects of the product offerings of major companies in the genAI music tool space, including OpenAI, Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Adobe.

Ethics and Public Distrust

Generating music with TTA sounds exciting and fun, right? However, there is growing concern that companies are not doing a good enough job of considering the ethics and minimizing harm before releasing AI-based tools for people to use ‘for real’.

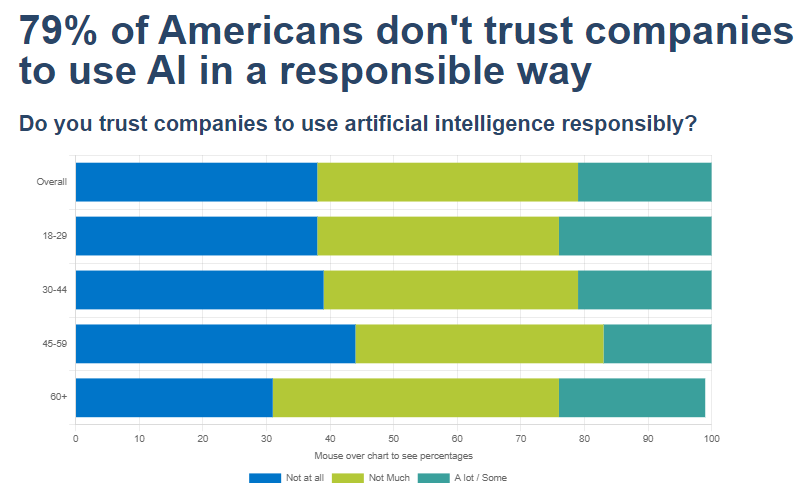

For instance, in the second annual Bentley-Gallup survey on “Business in Society”, released on Oct. 11, 2023, over 70% of US people surveyed (in all age brackets) distrust companies to use AI responsibly: they responded “not at all” or “not much”:

Since then, a March 5 Axios article noted that public trust in AI has continued to erode, in part because of growing concerns about whether generative AI is being developed & used ethically (not limited to music).

As “The Data Diva” Debbie Reynolds called out in her post on the Axios article, advocates are now calling on companies to move beyond the mechanics of AI to address its true cost and value: the "why" and "for whom". So let’s look at the PEOPLE affected by generative AI for music.

Why & For Whom

Stakeholders in generative AI for music fall into three broad categories:

Music ‘consumers’ who use the tools to create new works

Music ‘contributors’ whose original work is leveraged in building and using the tools

Tool providers and staff (including developers and researchers)

Individual people can, of course, belong to more than one of these categories.

In Part 7 of this article series, we’ll look deeper at how we can potentially evaluate balancing the benefits and harms to all three stakeholder groups vs. other potential benefits to society and the costs.

Music ‘consumers’

A wide variety of potential users of genAI music tools have been identified by various sources.

The envisioned use cases identified by the Adobe lead in the Adobe News item include “people [who] craft music for their projects, whether they’re broadcasters, or podcasters, or anyone else who needs audio that’s just the right mood, tone, and length”.

Meta’s Aug. 2 post on AudioCraft called out three potential users of the tool:

a professional musician “being able to explore new compositions without having to play a single note on an instrument”

an indie game developer “populating virtual worlds with realistic sound effects and ambient noise on a shoestring budget”

a small business owner “adding a soundtrack to their latest Instagram post with ease”

This article from justthink.ai dives a bit deeper into potential use cases than Adobe or Meta did, calling out:

Music Production (for composers and songwriters)

Film/TV/Advertising (generating soundtracks, scores, or brand music)

Podcasting/Voiceovers

Videogames/Interactive Experiences

Corporate/Creative Presentations

Education/Accessibility Use Cases (for teaching music)

Amazon’s “playlist partnership” with Berlin-based startup Endel, announced in Feb. 2023, addresses an additional use case: music for therapeutic or wellness purposes. More generally, as this Aug. 2023 article by Jerry Doby notes (not specifically about Amazon or Endel):“AI can be used to generate personalized tracks, adjusted to each person’s individual emotions and needs to create a therapeutic experience. It can generate calming melodies for anxiety relief, or upbeat tracks for motivation. It can even potentially analyze your reactions, preferences, and current behavior to fine-tune the music in real-time.”

Explorations of other therapeutic applications with generative AI for music are being reported in academia, for instance: “Exploring the Design of Generative AI in Supporting Music-based Reminiscence for Older Adults”. However, this use case doesn’t necessarily require ‘creating’ new content in the same way.

Setting aside for now the personalization and therapeutic features of functional music scenarios, it is obviously possible for most of these music consumers to achieve their goals of having just the right audio for all of these use cases by:

hiring a human musician/composer/producer for custom work, or

acquiring a license to existing music.

Implicit in most of these ‘music consumer’ scenarios is a desire to DIY (“do it yourself”) and inexpensively & quickly create soundtracks for unrestricted, royalty-free use.

Having said that, it seems logical that anyone who invests significant time in using an ethically-developed AI-based tool to create a song should be entitled to protect their ownership of their creation against misuse by others, if they wish. This aspect is legally complicated and has been less-discussed in western countries, particularly the USA, but has been of higher focus in China recently, as this article by Pranath Fernando points out.

Music ‘contributors’

Generative AI models and tools rely on existing music as training data. Composers and performers of music whose work is used as training data have a clear stake in how those tools use their work.

Music distributors or agencies who may own rights to a composer’s or performer’s music will also be highly interested stakeholders. (For now, we set aside possible legal and financial disputes between musicians and other entities who hold ownership rights to their work, on whether they can use AI-based tools to generate and sell ‘new’ material ‘by’ the artist.)

Although laws and policies and even public opinions can vary by region, in the markets where genAI tools for music are emerging, there is a general recognition that contributors and creators have some ownership rights to their work.

In addition to being music contributors, musicians could also be music consumers, i.e., users of genAI music tools. Composers, performers, and producers could create new content which they could market and sell.

The potential of AI for assisting musicians is logical. As this Adam4Artists article explains, “AI-powered music composition software can analyze a musician's existing work and suggest chord progressions and melodies that complement it. This can help musicians to experiment with new sounds and styles, without needing to spend hours writing and recording new music.”

However, it’s not clear that generative AI based on works by other musicians is required to achieve these gains.

Most genAI music tool providers have genuflected somewhat towards musicians as potential users. For example, although Adobe hasn’t strongly positioned its tool that way, they assert broadly that their tools will amplify creativity, and provide one demo video to touch on musicians’ concerns. The project lead at Adobe positions their preview tool as an “AI co-creator”.

Nonetheless, most of the excitement about Adobe’s tool (and others) centers on DIY use by non-musicians. Musicians are (understandably) raising questions about the impact on them. One has to wonder:

Are these genAI music tools truly solving any problems that musician creators want solved?

Or are references to musicians as potential tool users only “red herrings” to distract attention from the foreseeable harms to them?

Article update 2024-09-24: Consensus seems to have formed around two related frameworks for protecting the rights of creators (music contributors):

3Cs (consent, credit, and compensation) - Credit for the original 3Cs belongs to CIPRI (Cultural Intellectual Property Rights Initiative) for their “3Cs' Rule: Consent. Credit. Compensation©.”

4Cs (consent, control, credit, compensation) - Credit for the phrasing goes to the Algorithmic Justice League (led by Dr. Joy Buolamwini).

In future articles in this series, and on this newsletter for AI ethics beyond music, we will refer to the 4Cs, giving credit to both AJL and CIPRI. Earlier articles are also being updated with End Notes to give proper credit for the 3Cs and 4Cs frameworks.

Tool providers (and staff)

Ethical violations, including un-prevented biases, can cause great harm and can quickly derail an AI-based initiative. Part 2 of this series will explore these concerns in depth. For now, here are just two examples of bias-related failures in uses of AI for text:

An AI-based recruitment tool Amazon spent 4 years developing and testing was confirmed to be gender-biased and was shut down in 2018.

In a matter of hours, users manipulated Microsoft’s generative AI-based “Tay” chatbot into racism and Holocaust denial, and it was taken offline in 2016. Its new (February 2024) Bing chatbot has shown issues as well, and has been adjusted since its release to try to constrain misuse resulting in bad behavior.

If released prematurely, such ethical mistakes can cause grave harm to people and to companies before they are shut down or controlled. Although Microsoft and Amazon obviously survived these failures, harm was already done before they were disabled; and from a business perspective, such failures could be lethal to a startup or smaller enterprise.

Many developers and researchers who are working on generative AI tools for music and other domains are at the top of their profession and value their reputations. Participation or leadership in a public failure due to ethics or bias issues could be career-damaging. (For now, we set aside any legal questions about individual liability in such cases.)

A cold practical reality, though, is that even technically savvy staff in a development organization will not necessarily know where the data underlying their product comes from, or if it was obtained & used ethically. Many people in a development organization will not simply have visibility into where their product’s data comes from, or whether it is fair and representative.

As a result, for their own protection, all staff members should become ‘data literate’ and learn to ask questions about models they are using or developing or selling.

Tool provider companies have an ethical duty to ensure that their operations are carried out under “responsible AI” principles, top to bottom.

Tool developers, researchers, and other tool provider staff can and should learn to ask questions to ensure that they aren’t being asked to work on or promote tools built on unethically sourced or analyzed data.

Summary: Why & For Whom

Ethically protecting music contributors is not only important in itself, it is required (necessary but not sufficient) to properly protect music creators who use the tools to create new music, and to protect the people who develop the tools. Without “4Cs” protections for contributors, our music ecosystem cannot survive.

We believe 3 key ethical principles regarding WHY & FOR WHOM, one for each stakeholder group, should hold firm.

No musician should have the creations they own harvested and used without their knowledge, permission, or compensation by an AI-based tool, or have their creations used in an unethical or biased way (particularly if the use of their material creates the unfair impression that the musician endorses or supports the bias or unethical behavior, assuming they don’t).

It would be humanly impossible for musicians to track down misuse of their work inside corporations and models, and the burden shouldn’t be on them anyway.

No music tool user should have to bear the risk that all of the effort they invested into using the generative tools will be for naught if they lose their right to use (or sell) their creations or face legal exposure because the AI tool they trusted and chose:

violated a source creator’s rights, or

propagated biases embedded in the tool into their creations.

Expecting a large corporation to perform thorough due diligence on AI-based tools before selecting one is reasonable. Asking millions of potential AI tool users, most non-technical, to also do this is unrealistic (and inefficient).

No tool provider staff should have their reputations or livelihoods put at risk by being tasked with using or working on tools which are not being developed according to ethical, responsible AI practices.

Regarding the first and second principles, a colleague on Substack raised the point that belief in contributors’ rights (or creator’s rights) is an American or western value, which may not be shared globally. They proposed that in other countries, people may consider it acceptable for their creative contributions to be reused by the rest of the world without credit or remuneration.

I’ve reflected on this a lot (LOVE being connected to people who make me think and question my assumptions!) My conclusion is: Anyone who values free community reuse has an easy way to choose it for their own contributions or creations under western (or any) systems — simply release their works as public domain. Problem solved!

People who do hold that value of free reuse should not be entitled to impose it on others who do not, though. The global system we design should not require everyone to give up ownership rights just because some people may not value their rights. Rather, it should provide flexibility in allowing contributors and creators to control their rights. Given the global nature of our society, and the potential for people in one country to use a generative AI system trained on creative contributions from other countries with different values and policies, this seems the only viable path.

Bottom line: Providers of AI-based tools need to be challenged and expected to make it easy for contributors, users, and their staff to be confident that their ownership rights are respected and that use of the tool is ethical and as safe as possible.

In the meantime, we recommend:

Building awareness on ethics of generative AI, across the board. (This simple short course, part of Microsoft’s learning path in Career Essentials for Generative AI, is a good starting point if you have access to LinkedIn Learning.)

“Data literacy” initiatives, to help everyone build the ability to read, understand, create, and communicate data as information, and learn to ask good questions about tools they may use or build, can be part of the solution. Some resources:

HBS Online references on data literacy, building data science skills, and this free Beginner’s Guide to Data & Analytics

All potential music contributors, consumers, and development staff need to be aware of the risks they may be taking by using and building generative AI tools. (Late breaking news: see this March 21 announcement from the AI Vulnerability Database folks about an AI “algorithm auditing” tool for end users)

On that third point, in the next article in this series (Part 2), we’ll look at the risks we & these stakeholders are facing - whether we and they currently realize it or not.

What’s Next?

Here in PART 1, we’ve identified the key stakeholders impacted by generative AI for music, and how it can impact them (positively or negatively).

In PART 2, we will highlight some ethical risks faced by all three stakeholder groups (music contributors, music consumers, and music tool development staff) and explore applying the relevant AI ethics guidelines to genAI music.

In PART 3, we’ll survey the products and companies involved in genAI for music, including the major companies (e.g. OpenAI, Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Adobe) and some lesser-known enterprises from around the world.

See you there! (subscribe to be notified automatically when new articles in the series are published)

Acknowledgements - PART 1

Big thanks to the following for their kind contributions and feedback on drafts of this article:

While we’re working on Part 2, we’d love to hear from musicians, music lovers & consumers, technical folks, and people who are two or more of those! What do you think? Did we miss any important concerns that matter to you, or do you have a different view on some points?

You might be interested in reading about Aimi's approach: https://aimi.fm/the-ai-music-initiative.

This blog post provides a great explanation of IP rights of composers, performers, and production companies (our WHO): https://blog.bandlab.com/music-rights-insights-and-implications/